Hello Tooth Fans!

A very pregnant Dr. Kristie Lake here. 9 months in fact. I’m due in September, but he’s welcome to come any time because I am seriously in need of regaining my inner personal space. You wouldn’t believe how hard it is to sleep with a foot lodged in your rib cage!

I’m also looking forward to doing some of the things you can’t do when you’re pregnant – like eating deli meat, drinking Pumpkinhead (in moderation of course), and putting my sneakers on without sounding like Chewbacca.

What am I least looking forward to?

My next hygiene appointment and exam.

Why?

Not because Dr. Drews isn’t a kind dentist, and not because the baby took the calcium from my teeth – see my earlier post where I dispelled that myth – but because I have not been the best-behaved dental patient since this little alien took over my body. My sugar intake has gone through the roof, proving that dentists are people too, and sometimes it really is “do as I say, not as I do.” Doctors really do make the worst patients.

I’ve been great about brushing and flossing, of course, but the amount and frequency of sugar in my life has been embarrassing. So sometime after baby Riddle (Richard) is born, I’ll be making the walk of shame into the office to go get my updated X-ray pictures taken and find out if my brushing, flossing, and fluoride has kept up with the overload of acid created by my lack of willpower.

But if I do have cavities, then wouldn’t I know about it already? I am a dentist after all, right?! Oftentimes the early signs of a cavity are not visible to the naked eye, and the first evidence we notice, when cavities are between the teeth, is on a dental radiograph (X-ray). And, as Dr. Drews pointed out in this blog post, “Decay may be actively eating away at your tooth, but it won’t actually cause pain until it reaches the pulp or nerve.”

What are X-Rays?

X-rays are short for X-radiation, which is a form of electromagnetic radiation of high energy and low wavelength that can pass through solid objects, like your body, and will generate a black and white image (many shades of gray, really) based on the density of the object.

Very dense objects, like the metal from the crown you got last week, will show up white, or radioopaque, and less dense objects, like air or the infected tissue eroding away your bone, will show up dark, or radiolucent.

X-rays are considered ionizing radiation, which means they have enough energy to be able to knock an electron out of a molecule, making that molecule unstable. If this happens, there are 3 possibilities: 1) The cell dies (which is the desired effect with high dosage radiation used to kill cancer cells), 2) The cell repairs itself (the most likely scenario) or 3) The cell can retain the mutation and could later develop into a cancerous cell. The likelihood of any of these occurring is dosage dependent – i.e. – Not all radiation is created equal.

Let’s Talk Dosage

Prior to digital imaging, radiation was still relatively low compared to other medical imaging and even to other radiation sources we are exposed to in our everyday lives. With the advent of digital radiography, however, we are now using about 70% lower dosages to take our diagnostic images. Here at Drews we upgrade our technology all the time. We previously used a Planmeca ProMax 3D for our digital panoramic x-rays and currently use the Carestream 8100 3D for our panoramic and cone beam imaging.

Dr. Drews has talked about the subject of dental x-rays before, including information about the types of x-rays and some radiation dosage comparisons, but let’s talk about that again because it’s important! Let’s look at the actual numbers to see how they compare.

A dental radiograph exposes a person to .005 mSv (milli-Sieverts) of radiation (or 5 microSieverts). For reference, 1 Sv is an effective dose of 1 joule of energy in 1 kg of tissue.

Those numbers mean very little on their own so let’s place it in context.

There are natural sources of radiation we’re all exposed to all the time, from sunlight, to soil, to food. Just by existing on this planet, the average person is exposed to .01 mSv of natural radiation, double the amount of 1 radiograph. A flight from New York to L.A. exposes you to .04 mSv of radiation, double the amount of a series of bitewings.

But we don’t take dental X-ray images on a daily basis, or even every 6 months. We’re talking more like a year, or every other year, basis. And yearly, the background exposure to radiation you have just for the pleasure of being alive on this planet is 3.1 mSv, according to the Health Physics Society. That’s 620 times more than a single dental radiograph or 155 times more than a standard bitewing series.

In dentistry, we aim to minimize the risk and increase the benefit to all our patients. The radiation exposure that we use is kept to the ALARA principle, which stands for “As Low As Reasonably Achievable.”

There are evidence-based standards we adhere to for how often and how many radiographs we prescribe and we try to individualize these as much as possible to each patient’s particular risks and needs.

The dentist, knowing the patient’s health history and vulnerability to oral disease, is in the best position to make this judgment in the interest of each patient.

–ADA Recommendation Guidelines

Why Are Dental Radiographs Necessary?

Using X-rays to take dental radiographs is a significant part of the diagnosis of dental disease. There are some manifestations of disease processes we can easily recognize visually, like if you have a gaping hole in your tooth or if it is fractured to the gum line. But to understand the true extent of the examples I just noted, or to detect asymptomatic problems that are too small to be noticed visually, we require radiographic imaging.

When we forgo said imaging, either to lower the cost of the examination or to avoid any sort of radiation exposure, we can miss important information that then results in poor quality treatment, which in the long run is worse for your health, more expensive, and frankly unethical (because we know better).

Let me show you what I mean . . .

This patient had decay underneath a bridge. This decay was big enough that we were able to notice it visually. When there is decay under a bridge in that location (and that large) we would generally remove the bridge, remove the decay, and then remake the bridge. The patient had no symptoms, so there was no reason to suspect it was anything more than recurrent decay. And without this image, that would have been the treatment of choice.

But this image shows us the proximity of the decay (green) to the pulp chamber (or nerve) of the tooth (marked in red), which has caused the nerves in the tooth to die, and an infection is becoming visible at the bases of the roots (indicated by the blue arrows).

Had we simply proceeded with remaking the bridge, we would have missed the infection and performed an expensive treatment which would have ignored the undetected infection and ultimately made matters worse (and more expensive).

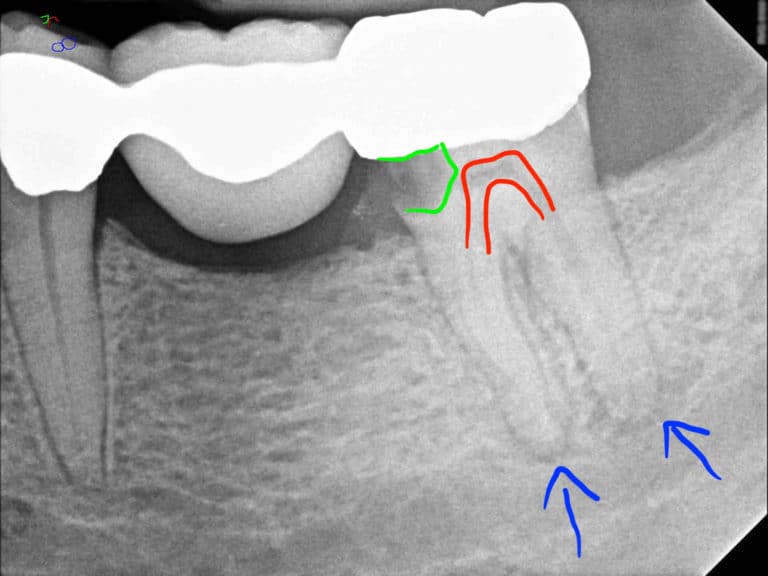

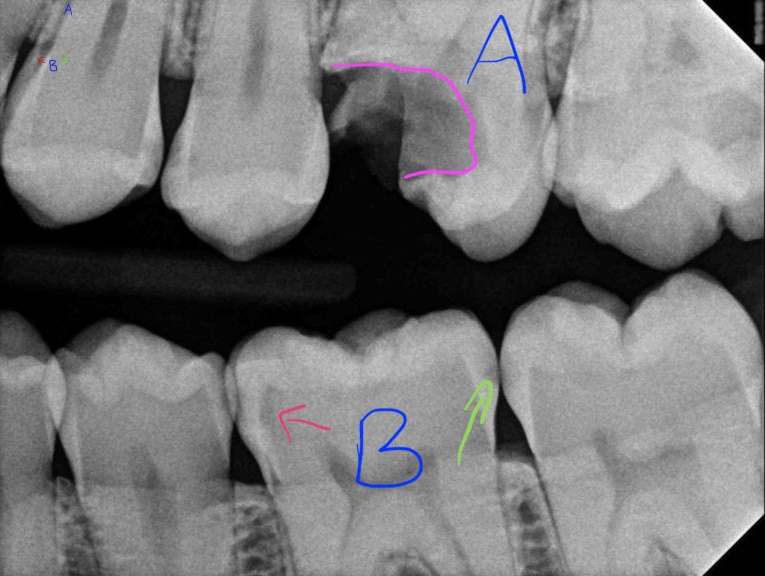

This next image illustrates the difference between a tooth with a visible cavitation, albeit extreme (tooth A), and a tooth with a cavity which requires treatment but is not visibly decayed in the mouth (tooth B).

Tooth A is in fact so broken that it requires more than a filling (root canal with crown lengthening and crown or extraction), but the patient was able to notice that this tooth was broken for some time, and as you would think, it was painful.

Tooth B did not hurt at all, but the green arrow shows an incipient lesion. That means the decay has started but has not yet progressed past the enamel layer (the white layer) and into the dentin (the gray layer). This is the start of a cavity which can be healed using high levels of fluoride in conjunction with good oral hygiene and dietary habits.

The pink arrow points to a cavity which requires treatment because it has moved through the enamel layer and into the dentin layer, which means it will only get worse if left untreated.

Notice that both these lesions are UNDER the white umbrella of enamel and as such are not visible to the naked eye. Waiting for them to hurt, or to make holes, would mean their size had increased significantly, making their subsequent treatment more extensive (perhaps root canal instead of filling, or a 3 surface filling instead of a 2 surface one) and more expensive.

There are many more reasons for taking routine X-ray pictures, from evaluating wisdom teeth to bone levels and pathology, and in all cases it is better to detect issues earlier rather than later, both for your health and your pocketbook.

Can I Refuse Dental X-Rays?

You are more than welcome to refuse any level of treatment, but it is vital that you understand the consequences of what you’re refusing. And while you can tell us that you’d rather not extract a tooth until it bothers you (though we wouldn’t recommend this), at least you’d be making a fully informed decision as to what the risks and benefits would be.

When refusing dental radiographs you are not really refusing treatment, you are refusing a diagnostic tool, which is like asking us to examine you with our eyes closed.

Legally speaking you cannot hold us harmless for NOT diagnosing you with a condition that we should have been able to detect using our clinical judgement. This means that you can’t just sign something saying you’re refusing the X-rays and as such we’re not liable for what’s missed. Not taking necessary radiographs, even at your request, is below the standard of care and as dentists we are held accountable. For that reason, while we can defer radiographs for a certain length of time (if we feel this will not put you at undue risk), we will sadly no longer be able to see you if you continually deny us the ability to ethically treat you with the care and respect you deserve (which includes routine radiographic imaging when appropriate).

For additional information, see the following publication by the American Dental Association – Dental Radiographs: Benefits and Safety!

Here We Go

There are 2 weeks left until my due date and I believe my cleaning is scheduled for October.

Hopefully, if it turns out the sugar has taken its toll, my cavities will look more like that green area on my bitewing radiographs (you know, the healable ones) than the pink ones.

I don’t like having my teeth fixed any more than you guys do, and Dr. Drews hates it even more because we usually do our own work in the off hours (lunch and evening) to keep patient slots available.

Wish me luck and I’ll talk to you all on the flip side of Mommyhood!

Love & Promising Your X-Ray Pictures Won’t Make You Glow in the Dark,